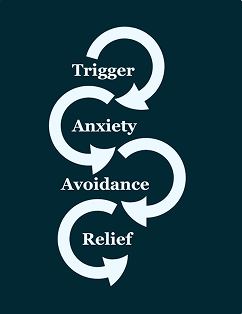

An "anxiety spiral" illustrates how anxiety becomes stuck in a loop despite your best efforts to manage it. In fact, anxiety tends to spiral precisely because of the efforts you use to manage it. Sometimes the spiral is obvious - you can clearly feel it coming and know what causes it to escalate. But often this spiral builds up in subtle ways because the strategies we think help actually ensure that the anxiety comes back stronger than ever.

Identifying these loops is the first step in starting to implement new solutions that will work for you. While it may be uncomfortable, it will ultimately help you cultivate healthier responses to anxious triggers.

key takeaways

- Anxiety can be unhelpfully maintained based on learned behavior throughout life.

- Despite providing short-term relief, unnecessary avoidance maintains the anxiety spiral.

- Unraveling the spiral of anxiety involves a counter-intuitive approach to triggering situations.

MEMORIES & LEARNING

The Development of Problematic Anxiety

While anxiety can be very useful, three pathways can contribute to it becoming activated too often, too intensely, and for too long:

- Modeling and instruction

- Traumatic experiences

- Evolutionary preparedness

Each of these pathways involves the brain’s capacity to learn from its experiences and use those memories to influence your behavior.

These memories get activated by present events that appear relevant to the past event in some way. When they influence action that hurts your life rather than helps it, we consider the anxious apprehension to have lost its value and no longer serve a useful purpose. Here’s a brief explanation of each pathway.

Modeling and Instruction

You can learn anxious behavior by watching others engage in their own anxious behavior (modeling) or by receiving messages that reinforce a particular type of anxious behavior (instruction).

This learning starts very early on in life and can be reinforced over the years into adulthood.

Examples:

- Modeled behavior can be seen in a parent who frequently washes their hands after everything they touch. Your brain flags those experiences as significant for your health and you start to develop a growing vigilance toward germs and cleanliness.

- Instruction can be seen in a parent’s regular commentary on how “it’s better to be safe than sorry” whenever planning what to bring on large trips. If your brain flags this as an important message for risk-aversion, it may retrieve it whenever you plan to go on vacation, causing you to anxious over-prepare.

We all pick up on ways of being in the world by observing others.

There’s simply no avoiding learning unhelpful behaviors at some point throughout the course of your life as you engage with different people in different situations. The challenge, however, comes in starting to identify what messages are no longer useful and in need of updating.

Traumatic Experiences

Unlike modeling and instruction, trauma involves your direct experience with a highly aversive object or situation that causes you to fear for your safety or security.

The brain will learn to automatically respond in self-protective ways whenever there is a present trigger reminiscent of this past traumatic event.

Examples:

- Being attacked by an aggressive dog. After such a situation, the brain has learned to associate the previously non-threatening presence of dogs with now being very likely to lead to physical injury. Any dog, regardless of breed, may now become a trigger for anxiety.

- Being yelled at by a parent. If a child is unable to physically escape to safety, the brain will learn to freeze, dissociate, and mentally shut down in similar situations to protect against the verbal abuse. As an adult, this same response can become activated whenever someone is frustrated or there’s the potential for even a minor confrontation with someone.

However, traumatic experiences are not guaranteed to cause long-lasting problems with anxiety.

Positive experiences and familiarity with an object or situation have been shown to be protective factors against developing excessive anxiety following a negative experience.

Research has shown that being bitten by a dog, for example, is less likely to produce a dog phobia among those who have had prior contact and familiarity with dogs and their behavior (Doogan & Thomas, 1992).

Nevertheless, traumatic experiences are a significant contributor to problematic levels of fear and anxiety.

Evolutionary Preparedness

Finally, there are certain universal threats to human safety that appear to be hard-wired into the brain’s fear circuitry based on our evolutionary past.

Fears related to venomous creatures, falling, suffocating, or being rejected from a group tend to elicit a more potent fear response than more recent threats to our safety, such as automobiles and firearms.

Despite the fact that there have been an estimated 40,000 automobile-related fatalities in the United States over just the past few years (Fatality facts 2021: Yearly snapshot, 2023) and less than 3 spider bite fatalities per year (Spider bites, n.d.), there is still a generally higher aversion to spiders than to driving.

Despite this predisposition to certain fears, however, what is most likely to influence whether it sticks around and interferes with your life is your own personal experience with them. If you have a significant negative experience with one of these predisposed fears, it can loop back to the previous pathway regarding trauma and its impact on your sense of safety and security.

HOW PROBLEMS PERSIST OVER TIME

The Anxiety Spiral

What maintains the repeating cycle of anxiety is often your efforts to rid yourself of the discomfort.

It may feel like you have strategies that help you cope with the anxiety because they bring relief. But it’s precisely those strategies that leave room for the distress to return in the future.

Rather than give up these strategies in favor of a more successful approach, we tend to double down and use them even more because of the belief that they should work.

Let’s look at how this leads to a spiral.

1. Triggering Event

When unpacking an anxious experience, it’s useful to start by asking what set it all in motion. What was happening just before you started to feel anxious?

The reason for this is that your brain picked up on some bit of information that it interpreted as potentially harmful to your wellbeing and started a stress response to deal with it.

Examples of triggering events:

“I noticed an unexplained pain in my body, causing me to feel uncertain about my health.”

“I was waiting to give a presentation at work, causing me to feel uncertain about the group’s perceptions of me.”

“Someone didn’t respond to a text I sent, causing me to feel uncertain about whether they’re mad at me.”

“I had to use a public toilet, causing me to feel uncertain about whether I have germs on me.”

Each of these triggers brings some feeling of uncertainty that’s hard to manage that generates anxiety as the brain attempts to get you to do something about it.

2. Anxious Response

Anxiety is your brain’s attempt to grapple with an unknown future. It’s the “activation energy” in your body that helps you make sure these unknowns become known so that you may avoid negative consequences.

Your nervous system has the capacity to experience anxiety for a reason.

For more information on this, you can also read my article on The Fear Network: How the Brain Influences Behavior.

But once it reaches a certain threshold, this activation energy can paralyze the senses and render them unusable. The discomfort becomes a vague and unspecific apprehension that can make it difficult to say what you’re actually concerned about. As a result, the brain starts looking for some way to avoid this distress and alleviate the discomfort.

3. Avoidance

Avoidance is one of the most common strategies we use to try and resolve the discomfort of anxiety.

Sometimes it’s necessary and helpful to avoid situations that may bring undesired outcomes. It may be appropriate, for example, to avoid unusually loud noises in your immediate vicinity, or to avoid someone who is threatening to assault you, or to avoid going to isolated areas with people you don’t know.

These types of avoidance are healthy and don’t contribute to recurring anxiety after the potential threat is gone. What maintains a spiral of endless anxiety that doesn’t resolve itself is avoidance when it’s not needed.

Examples:

Worrying

Reassuring self-talk

Avoiding feared situations

Bottling up feelings

Excessive attempts to control things

Procrastination

Using drugs or alcohol

These provide temporary relief, but don’t address the core experience that is actually causing the anxiety.

Treatment targets for anxiety aren’t necessarily about reducing the experience of anxiety. They’re about helping you learn to stop engaging in avoidance behaviors when they’re not needed.

If avoidance becomes the guiding principle behind your actions, then you remove the opportunity to regain a healthy perspective over anxiety-provoking situations, to build your tolerance of things that are uncomfortable but not dangerous, and to build confidence in your abilities to handle such circumstances.

4. Reflief

The challenge with anxiety spirals is that the solutions you may have been using to avoid this discomfort bring some sense of relief! They work, even if it’s only temporary.

This relief from the discomfort is what’s called negative reinforcement.

The brain learns that whatever you did helps to reduce anxiety in the moment and will prompt you to do the same thing next time. In these situations, your brain doesn’t care that they’re not viable long-term solutions because it’s more concerned about your immediate security.

Stopping the spiral means recognizing that, even though these strategies bring relief, they leave you no better prepared for next time. A new approach is needed that is not solely focused on avoiding discomfort.

A NEW APPROACH

Stopping the Spiral

The paradoxical approach to getting out of this spiral is to stop pulling away from the anxiety and allow yourself to move in closer.

By changing your position regarding anxiety, you send the message that you no longer have to stay on guard against it.

What attitude should you have?

One that is counter to what anxious thoughts tell you.

One that wants opportunities to increase your tolerance of uncomfortable feelings.

One that confidently faces difficulties.

One that is patient, compassionate, and supportive.

The idea is not to cope with the anxiety, but to deliberately allow yourself and invite feeling anxious.

This counter-intuitive stance helps to stop the spiral of anxiety through a process called inhibitory learning.

New learning about yourself, others, situations, and outcomes inhibits the old learning.

While it may be deeply unpleasant, it’s about cultivating a mindset of wanting anxiety as an opportunity for new learning.

“I want the opportunity to build my confidence in the face of uncertainty.”

“I want every chance I can get to practice being the type of person who can face anxiety.”

“I want to show the anxious part of me that I am capable of living my life without it telling me what to do.”

“I want to practice rebelling against old messages I have learned.”

“I want to build my tolerance of discomfort so that I don’t have to avoid.”

“I want the opportunity to show my body that it is safe.”

All of these require me to have the anxiety, so if I’m going to have it, let’s have it.

Much like going to the gym to get stronger, there’s value in the discomfort. You don’t take on too much weight all at once, but willingly take on these gradual opportunities for growth.

CONCLUSION

Don’t Needlessly Trigger Yourself

Gradual inoculation against distressing, non-dangerous situations is very useful, but deliberate exposure to situations that are flooding, overwhelming, and traumatizing is unnecessary and unhelpful. You want to build your confidence, not put yourself in situations where you continue to feel helpless and powerless.

Small movements are going to be useful in sending easily-integrated bits of information back to your brain to strengthen your tolerance of uncomfortable experiences. A well-trained therapist can also help you navigate this process. Allow yourself to listen to your body and gradually expand its capacity to hold difficult sensations and feelings. A shock with too much intensity is never good or useful.